In the basement family room of my wife's Iowa farmhouse is a pretty standard collage of family photos. Some are of now nameless turn-of-the-century relatives; some are fairly recent of growing grandchildren. In one section are three perfectly level rows of six 5x7 photos corresponding to the six Kahlstorf children born to Harold and Faye. Three each of my wife and her five brothers; eighteen pictures in all.

The arrangement for four of them fare identical: a childhood picture, a high school graduation picture and a wedding picture. The two exceptions are Jeffrey, who died as a little boy in a farm accident, and Keith who was killed in Vietnam 40 years ago this week.

In lieu of Keith's wedding picture there is an official Marine photo, the standard pose of a scared recruit a few days into basic training. Those official military photos you see in newspaper releases are anything but casual; the new recruits are marched in, a fake uniform is rapidly draped over them and they are commanded to stare straight ahead. The whole photo opp takes less time than it took me to compose and type this paragraph.

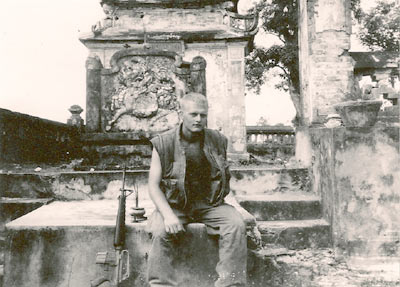

Except for the uniform, Keith's Marine photo is not appreciably different from his high school graduation photo taken a mere two or so years earlier. But tucked inside the frame is a faded, color 3x5 snapshot of him in Vietnam. It's not a posed picture, rather one of those random, relaxed shots likely taken on impulse. Keith is sitting relaxed on the grounds of a Buddhist temple, helmet beside him and M-16 rifle cradled in his arms. He is in the standard olive drab, sweaty fatigue uniform with the sleeves cut off. Without his helmet you can see his eyes.

Unlike his official photo in the frame Keith is smiling a bit - more like a slight grin. If the picture was taken today with a digital camera in Iraq or Afghanistan you can imagine a scoffing 'hey dude what are you doing?" Days later he was killed in a mortar attack. He was twenty years old.

Keith was five years older than my wife and she tells of a sad May day when she was called out of ninth-grade biology to report to the principal's office. She was nearly a perfect student and her peers were perplexed at this uncommon invitation. She was also confused and that confusion grew when she saw her father crying in the hall. When she stepped out he exclaimed, "They got him! They got Keith!" He had to be specific because her brother Gary was also serving in the Marines in Vietnam.

As small farming communities do Britt, Iowa embraced her family and mourned the loss of one of their own. The county schools closed and recent classmates made the pilgrimage home. The crowd at the funeral was huge. It is hard to imagine anyone who did not set aside spring planting or shuttered their shop or store to attend.

At the graveside service Scriptures were read, prayers were offered and then sharply dressed Marines folded a flag and fired a 21-gun salute with absolute precision. Mournful taps were played, and hugs, tears and promises of support were exchanged.

Then life did what it always does in those circumstances, it moved on.

When I joined the family many years ago little was spoken about Keith. Over time I grew curious and have tried to piece together a composite picture of his personality.

Physically he was about my size, perhaps a bit taller and we shared a shoe size. His service boots, likely the ones he died in, were sitting unused in the basement and they fit me perfectly. They didn't fit his three brothers so my mother-in-law gave them to me and I used them mostly for hunting. Looking back I sort of regret using them, while practical it now seems a bit irreverent. But when I was sitting quietly in a deer blind it was hard not to stare at them and think about this brother-in-law I never knew.

Once I was speaking at a training conference for teachers. In the context of my talk I somehow referenced Britt, Iowa. At the break a middle-aged woman introduced herself to me as having grown up in Britt. The town is small and she obviously knew the Kahlstorf's and as it turned out she graduated the same year as Keith. So in the few minutes we had to talk I curiously asked her to tell me about him. What was he like in high school? What did she remember about him?

She paused and answered and even rambled a bit as we are wont to do when caught unawares with thoughtful questions and after a minute or two she finished. Then she began quietly crying. Then for some reason she hugged me and offered the highest compliment any human being could receive. She said she missed Keith and wished he were still alive.

Keith Kahlstorf was a hard working farm kid - the last of a generation who grew up on a completely self-supporting farm. His efforts were needed on the farm and in between he managed a social life centered around his high school. He was a decent student but a very good wrestler, a state champion in fact. He was a dutiful son, a helpful big brother to my wife and almost certainly a good marine. He dreamed of finishing college and becoming a schoolteacher and wrestling coach. But the fateful combination of a draft and a mortar shell put an end to that dream. He was twenty years old.

I grew up in a military home and lived in Germany in the early sixties. Having no television we frequently went to the base theater on Friday nights and watched movies. They were the movies you now see on the TNT channel, movies you could take your children to without being embarrassed. My favorites were those World War Two movies often staring such notables as John Wayne and Kirk Douglas.

Afterwards my friends, other sons of sergeants, and I would reenact those movie scenes in fields outside our quaint little German village. Using rocks for grenades and whatever toy guns we could scrounge, we played war. Sometimes we fought the Japanese, but mostly we fought the Germans - it was convenient. But for us war was a game. Causalities were common but somehow we all lived to fight and play another day.

In the summer of 1962 our family went on a three or so week camping trip in southern Europe. There were six of us plus a tiny grandmother squeezed in a big Buick. I was eight or nine years old at the time and once, while winding our way through the hills of northern Italy we made a surprise stop at a military cemetery. When the door opened and we flowed out and I cared little about the site except for the reprieve from sitting.

Looking back that was the first time I connected war with death. Up until then it was entirely a game.

Many years later, after college and seminary, I went on to earn a graduate degree in American history focusing part of my studies on America's wars. Even later I spent a year studying at the Air War College, one of our nation's schools for senior officers. In between I befriended war veterans and listened to their stories.

More recently, and somewhat to my surprise, as a Reservist I deployed twice - once to the Afghanistan theater and once to Iraq. As a chaplain I conducted memorial services, listened and prayed with those who were injured, comforted those who were scared and counseled those who felt guilt over killing.

Thus I have had the relatively rare opportunity to not only study war in a formal sense, but to engage in it at a very personal level. While trite to say, it does put a whole new perspective on it. Thus with the combination of experience and diminished testosterone, I now view war differently than when I joined the Kahlstorf family.

In what can only be considered poetic irony I am indebted to the infamous communist leader Joseph Stalin who best sums up my current feelings. He is quoted as saying, "A single death is a tragedy, a million deaths is a statistic."

Keith was killed in the 3rd week of May in 1969. Life magazine, then a powerful media presence, took an editorial position against the Vietnam War and in the June 27th issue published a pictorial collection of everyone who died in Vietnam that third week of May. There on page o is Keith's official photo along with a caption which gives his name and home town. There were 227 pictures printed.

In my studies of war casualties are statistics. Hopefully not mere statistics, but statistics nevertheless. It's hard to put your emotional hands around hundreds or thousands of war dead. But when you are connected with a single war causality - war becomes tragic. Absolutely tragic.

As a chaplain there have been times when I've made home visits to share the distasteful news that a son was killed in action. I can recall each one of them in minute detail. Without exaggeration I have literally held the hand of a soldier as he bled to death.

Now when we visit Britt, Iowa, just before we leave, I make it a point to go down to the mostly unused family room and stare at the pictures. I look at them all, some of my family and they generate warm memories.

But before I leave I stop and stare at Keith's piercing eyes. I suppose it is my way of memorializing him duty and his sacrifice. When I joined the family I saw in that picture a peer for I was close to the same age as that steely-eyed Marine in the picture. As the decades elapsed my vantage point shifted and I saw him as a younger man. Enough years have elapsed that I now stare at that picture and see "a kid" as colonels my age are prone to call wonderful and brave young marines, soldiers, sailors and airman. Our daughter is now his age and our son just a few years older.

And I wonder what life would look like if the mortar had missed. Or even better if there hadn't even been a war? What weddings and births would have occurred? What friendships might have developed? As a teacher and coach, what kids might he have impacted? How much richer would our world be if Keith Kahlstorf had lived past twenty?

They are useless, futile musings. Questions of speculation. But I do wonder.

Last summer I was playing golf in her town and my chance golf partner was also Keith's peer. I asked the same questions and for two or three holes he recalled stories from their childhood and then, as he was ready to tee off on the third hole he looked at me and mentioned that it just struck him that his son was now twenty - the age Keith was when he was killed. He then turned away and stared into the adjacent cornfield for a few moments. I left him in his silence and thoughts and when he was ready he wiped an eye, turned around and we teed off. Nothing more needed to be said.

"I find war detestable but those who praise it without participating in it even more so"

Romain Rolland quotes (French Writer, 1866-1944)

"A single death is a tragedy, a million deaths is a statistic."

Joseph Stalin quotes (Russian Prime Minister,

Communist leader and Political Dictator.

Governed from 1929-53. 1879-1953)

Lt. Col. Stanley Giles, Chaplain,

Iowa National Guard, Nov 24, 2014