| |

|

|

|

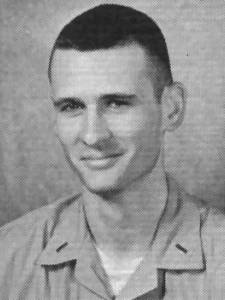

Robert Ray Duncan

Lieutenant

VA-85, CVW-6, USS AMERICA, TF 77, 7TH FLEET United States Navy West Palm Beach, Florida March 16, 1942 to October 22, 1975 (Incident Date August 29, 1968) ROBERT R DUNCAN is on the Wall at Panel W46, Line 57 See the full profile or name rubbing for Robert Duncan |

|

|

| |

|

LTJG Bob Duncan joined Attack Squadron Eighty-Five (ATKRON 85 or VA-85, squadron callsign BUCKEYE) after the squadron's 1967 Viet Nam deployment. On his first combat cruise, Bob was teamed with a second-deployment bombardier-navigator, LTJG Al Ashall. Homeported at Naval Air Station Oceana (Virginia Beach, VA), VA-85 deployed in USS AMERICA (CV-66) in early 1968. Following work-ups, we proceeded to the South China Sea via Rio de Janario, the Cape of Good Hope, and the Indian Ocean, arriving at Yankee Station on 12 May 1968. VA-85 had 15 INTRUDER aircraft, 12 A-6A bombers and 3 A-6B SAM killers. These three aircraft were partially stripped of the normal DIANE navigation and attack system, and instead were fitted with surface-to-air radar detection equipment and the gear needed to effectively use the Shrike and long-range Standard ARM (Anti-Radiation Missile) missiles. Four crews, including Bob Duncan and Al Ashall, had qualified on the A-6B in addition to their normal A-6A qualifications. Initially, the A-6B's were used in the same manner as the equivalent USAF Wild Weasel aircraft: they accompanied daylight strike forces as advance Iron Hand and SAM suppressors. Normal weapons configuration was 2 Shrikes on the outboard wing pylons and two Standard ARMs on the inboard pylons, with a drop tank on the centerline. Because of the scarcity of the Standard ARMs, we were encouraged to use them only when a really promising target came up, and then only if the target was beyond Shrike range or if the Shrikes had been expended. As the cruise progressed, VA-85 increasingly found itself tasked with night single-aircraft missions over North Viet Nam - exactly what the aircraft was designed for. However, the inability of the A-7As and F-4Bs to operate effectively over land at night meant that there were fewer aircraft over the beach, and consequently these few aircraft drew more concentrated attention from NVN's anti-air defenses. The A-6B tactics evolved accordingly. An A-6B would launch with the attack birds, and everyone would go their separate ways . . . the attack birds at low level and the A-6B wandering around feet dry at 20,000 feet or so. If and when the NVN gunners lit off their fire control radars, the A-6B would attempt to engage them with either Shrike or Standard ARMs. Given the limited number of A-6Bs, these missions grew to "double-cycles" - launch and go over the beach with the first batch, go feet wet to refuel when they went home, and be back in position as the second wave came feet dry. As the weather worsened, the A-6As would operate below the cloud cover while the A-6B would remain above (or in) the clag. This situation exacerbated the A-6B's weakest point: a combination of detection system and missile delivery parameters left the A-6Bs vulnerable to a close-in attack from the rear hemisphere. If the A-6B found itself targeted from the rear, SAMs might arrive before the Shrike or Standard ARM missiles could take out the SAM guidance radars. If you were operating within the cloud layers and couldn't see the SAMs, dodging them became a very tricky affair. On 29 August 1968 Bob Duncan and Al Ashall were scheduled for one of these missions, a double-cycle in support of two A-6A waves. The first wave came and went with no SAM activity, and the A-6B joined with an EKA-3D to refuel before going feet dry to await the second A-6A wave. Between the A-6B's "Feet dry" call and the arrival of the second A-6A wave, the EKA-3D recorded SAM missile radar activity. As usual, the on-station EC-121 flight following aircraft had lost radar contact with the Buckeye SAM killer after it went feet dry. No calls were heard from the Buckeye A-6B, and it failed to return. What happened? What is known is simple: The Buckeye flight went feet dry and was not heard from again. What may be surmised is equally simple: The NVN air defenders waited it out until the A-6B was alone over North Viet Nam and then took it under fire from the rear quadrant. While the weather low was reasonable, heavy towering cumulus and high layers blanketed North Viet Nam that night -- the worst possible situation for SAM-dodging. It appears likely that the hunter became the hunted, and lost a missile exchange. Bob was carried as "Missing in Action" for seven years; on 22 October 1975, his status was changed to "Killed in Action". A-6 aircrews were accustomed to operating alone, without radar flight following or other friendly support. Bob and Al recognized the inherent risks and accepted them without qualm. Their professionalism and dedication to duty warrants our respect. Bob was more restrained and more married than many of the rest of us, which made for quiet liberties. Never the less, he was a solid officer, a professional aviator, a good friend, and very well liked. Thirty-two years later, his death in combat still brings a sense of sorrow and loss.

From a friend, squadronmate, roommate, and fellow VA-85 A-6A/A-6B aircrewman, |

|

I was a Marine Sergeant in Vietnam when Lt. Duncan went down.

Glenn C. Davis |

|

I was a Jet Engine Mechanic for VA-85, on the America, and knew both Mr. Duncan and Mr. Ashall. My heart and prayers are always with them, and they are my sanity from an insane era. Men like these are why men still go to war, to defend what we are blessed to have.

Brian Lake |

|

I have never tried to find out information on the man whose name is on the bracelet I have worn for 22 years. I have had the bracelet fixed 3 times and buffed so it would shine again. I have prayed for him and his family countless times. I have many family members who have served in our armed forces including my husband and currently my son is a US Marine. Thank you for the opportunity to find out more information about this fallen soldier.

Cindy Perez |

| Contact Us | © Copyright 1997-2019 www.VirtualWall.org, Ltd ®(TM) | Last update 08/15/2019. |