Robert Moffett DowlingChief Warrant Officer197TH AHC, 145TH AVN BN, 12TH AVN GRP, 1 AVN BDE Army of the United States 22 July 1938 - 12 January 1966 Centralia, Washington Panel 04E Line 067 |

|

|

The database page for Robert Moffett Dowling

REMEMBEREDby his friends and family.

A memorial initiated by his son, |

From The Daily Chronicle, April 30, 1966"Lewis County's first casualty in the Viet Nam war, Chief Warrant Officer Robert M. Dowling of Chehalis, was posthumously awarded four medals in an impressive ceremony April 21 at Fort Lewis. The medals were received by Dowling's widow, Mary, on behalf of her husband. Maj. General Arthur S. Collins, Jr., post and division commander at Fort Lewis, presented the medals and was himself impressed with the gallantry of the Lewis County serviceman. "This is the largest number of decorations I have had the privilege to present to one person at one time," the general said. Dowling died in Viet Nam Jan. 12, 1966 from wounds received in action. The medals he received include: The Purple Heart, for wounds received in action which resulted in his death; the Bronze Star for Valor - for heroism in ground combat on Jan 1, 1966; the Distinguished Flying Cross - for heroism while participating in aerial flight in Viet Nam on Sept. 30, 1965; eight oak leaf clusters to the Air Medal (each cluster signifying 25 combat aerial missions over enemy territory in support of ground forces), the Vietnamese Cross of Gallantry with palm - presented by the Republic of Viet Nam (in December) for heroic action against the enemy, and a company plaque presented by the officers and men of the 197th Armed Helicopter Company. The acts of heroism which resulted in the medals for Dowling read like chapters out of a thrilling war novel. For example, this was the action that lead to the Bronze Star:"...Dowling distinguished himself by exceptionally valorous actions on 1 January 1966 while serving as co-pilot of an armed helicopter during combat operations near Tuy Hoa. When his helicopter was shot down by Viet Cong .30 caliber automatic weapons fire, Dowling suffered a badly sprained left hand and a severe blow to the head. Although he was seriously wounded he salvaged one grenade launcher and one rifle, and returned devastating fire in the Viet Cong automatic weapons position surrounding the crash site until his ammunition was expended. Then, with complete disregard for his personal safety, he exposed himself to the insurgent position and painfully made his way back to the downed aircraft to secure more ammunition. Refusing medical aid, he returned to his position and silenced a Viet Cong automatic weapon. When a rescue helicopter landed, Dowling provided deadly fire cover and refused to leave his position until the remainder of his crew was safely aboard the aircraft..."And an excerpt from the Distinguished Flying Cross award: "...Through his courage, dedication, and outstanding marksmanship, he contributed immeasurably to the successful completion of the mission which saved many lives..."The company award was in recognition of "outstanding performance of duty while logging 251.7 combat hours and 291 combat missions." Dowling attended Chehalis schools and graduated from W. F. West High School in 1956 and from Centralia College in 1958. He also attended the University of Washington and worked as a pilot for a number of business firms. Because he loved flying, he decided to make the U.S. Army his career and was commissioned a warrant officer when he joined in 1963. By then he had already fulfilled his military obligation by serving seven years in the Marine Corps Reserve. He was sent to Viet Nam from Fort Lewis in June, 1965. The helicopter pilot was married to Mary Garrison, daughter of Mr. and Mrs. Dayton B. Garrison, Centralia, in 1958. They have four children- Bonnie, 3; Susie, 4; Bobby, 5; and Laurie, 6. Attending the award ceremony at Ft. Lewis with the widow were her parents, Mr. and Mrs. Garrison; her husband's parents, Mr. and Mrs. Tad Dowling, Chehalis; David Dowling, Tacoma, a brother, and other relatives." |

Families and friends of war victims unite in memory of loved onesBy CANDY HATCHERSEATTLE POST-INTELLIGENCER COLUMNIST Monday, December 3, 2001 FORT LEWIS -- No one knows who is buried in the center of the cemetery, in the grave marked "unknown soldier." Whatever links that soldier had to family and community were lost with his death. But a few hundred feet to the left, past plots of sergeants and privates and captains and majors, lies the marker for the grave of Robbie's grandpa. It doesn't say that, of course. But Robbie, 6, knows it because the name on the headstone is his name, too: He's heard lots of stories about his grandpa, how he was a helicopter pilot and a hero in Vietnam, how he saved lots of people's lives before his helicopter crashed in 1966. He's heard his grandpa was a really nice man who played games with his children and laughed a lot. But Robbie never got to meet him. His grandpa died at 27, when his son, Bob -- Robbie's dad -- was only 5. It's hard to grasp the meaning of war when you're just a kid. You know only that it can take something big from your family, and you don't get it back.

You struggle through the father-son camping trip with somebody else's dad. Somebody else teaches you to throw a spiral, to calculate batting averages, to bait a hook. It's those losses we often forget when we look at war's toll on America. The severed relationships, the missing pieces from our past. We can look at the numbers from any world conflict, including the Sept. 11 attacks, and marvel at the loss. But until we know the names and the stories, until we meet the widow who never remarries, and the four children who grow up without a father, and the 6-year-old who knows his grandfather only through pictures, we can't fully appreciate the enormousness of America's sacrifices. That is war's challenge, today as much as a half-century ago: To look beyond the flags and displays of patriotism to what we're sacrificing -- family members, friendships, links to history -- and why. And to make sure they're not forgotten. It's why Bob Dowling called Ted Branstetter, a friend of his father's he found four months ago by coincidence and asked to meet at the cemetery. It was time to pay tribute to a man they both loved, and to give Robbie a sense of history. CHIEF WARRANT OFFICER Robert Moffett Dowling died nearly 36 years ago, flying a rescue mission for the U.S. Army, but long before that, he was a Marine with a strong sense of duty and an equally strong sense of fun. When Bob Sr. and Ted Branstetter met at Sand Point in the mid-1950s, Ted was a staff sergeant, responsible for training and drilling groups of recruits for 11 weeks and then sending them off for duty.

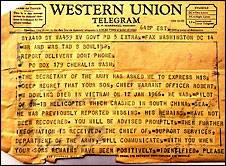

When Bob Sr. and Ted Branstetter met at Sand Point in the mid-1950s, Ted was a staff sergeant, responsible for training and drilling groups of recruits for 11 weeks and then sending them off for duty. Ted was five years older than Bob Sr., a Chehalis pilot he thought of initially as "just a grunt in the group." But Bob had a wonderful sense of humor that drew the two together. He remembered telling Bob, "you wouldn't make a pimple on a good corporal's ass." And Bob simply smiled and said, "Oh yeah?" and shot Ted with a grease gun. That started a grease fight in the hangar. "We had quite a mess to clean up," Ted said. "In retrospect, I wish I'd paid closer attention to those things." Ted and Bob lost touch after Bob, with seven years in the Marine Corps Reserves, got out in late 1962. Ted knew Bob had earned the Marines' Good Conduct Medal. He knew Bob joined the Army and eventually went to Vietnam. He didn't remember that Bob had children. Bob's son has vivid memories of those days, however. "Dad used to walk around Fort Lewis in his flight suit holding my hand. We'd go to the barber shop and get the same haircut. I had a little uniform exactly like his. And when he went to Vietnam, I wore it every day. "He was my hero." The night before Bob Sr. left for Vietnam in 1965, he sat with his son, then 4, and told him he was the man of the house, and to take care of his mom and three sisters. He was going to war, he told the child, and he might not come home. "He knew what he was getting into," the younger Bob said recently. He started his tour of duty Jan. 7, 1965, and died one year and five days later -- the first Lewis County man to die in the Vietnam War. The telegram came by taxi. It said Chief Warrant Officer Dowling had been piloting a UH-1B helicopter that crashed in the South China Sea. He was buried at Fort Lewis. An Army general presented Bob's widow with his medals: A Purple Heart, Bronze Star, Distinguished Flying Cross and eight oak leaf clusters to the Air Medal. Eventually, his name was etched on Panel 4E, line 67 of the Vietnam War Memorial in Washington D.C., and on a smaller, traveling replica that came to Bellevue the last weekend of July. And that's where Ted found the missing pieces. THE WHITE-HAIRED Marine sergeant stopped by a restaurant in Bellevue that Saturday and noticed servicemen in dress uniform. They were serving as the honor guard at the traveling wall, they said, and encouraged him to visit.

Ted, 68, hadn't planned to go, but it was on his way home. He stopped by the park and looked up the name of his old Marine buddy in the index. He'd heard Bob had died in Vietnam shortly after his tour began. He wanted to pay his respects. A Boy Scout took him to panel 4E, where he waited in line to reach the wall. He was talking, as is usually the case, telling the boy about his friend the helicopter pilot who had flown the Huey. At that moment, Bob Dowling, the 40-year-old son, was at the traveling wall, too, helping his son Robbie, then 5, and daughter Michelle, 6, take an etching of their grandfather's name. "This older gentleman came up out of the blue and started talking about his good friend, telling the same kinds of stories I told about my dad. I was thinking: 'That sounds like my dad's story. He rescued a lot of people. He flew the Huey. He served as a Marine reservist and then became an Army helicopter pilot.' "I heard amazing parallels. The guy was saying, 'And all I know is, he was killed in 1966 and he was a great friend of mine.'" Bob, who is the spitting image of his father, stood up, removed his sunglasses and said, "I believe you're speaking of my father. I'm Bob Dowling." Ted started crying. "I couldn't help it," he said. "We hugged. He's like a son of mine, an extension of family somehow. I had immediate love for this guy." Bob told him he had been praying and looking on the Internet for someone who knew his father. He even had posted a memorial on a Vietnam War memorial website. What are the odds that these lives would intersect here? A week earlier, Bob had moved his family to the Seattle area from Virginia. What if they had moved a week later? What if Ted had showed up a few minutes later, or the next day? Call it coincidence, or call it the hand of God. But something really special happened at that wall that allowed a son to learn about his father -- and a grandson about his grandpa -- from a man who knew him 40 years ago. The next day, the two met again at the wall, and Ted brought pictures of Bob's dad. "It was a gift," Bob said. "A significant one. This was meant to be. We're picking up where my dad and Ted left off." TED WEARS A BUTTON on his jacket: "I Believe in America." And he does. Service is in his genes. The Bellevue native and divorced father of five spent 16 years in the Marine Corps and earned the Distinguished Flying Cross. He knows every inch of a helicopter. His father was at Guadalcanal in World War II, and for the past 11 years, his daughter has been an Army helicopter pilot -- she's the same rank Bob Sr. was when he died. One afternoon in 1968, when Ted was still in the Marines, he remembers being stopped in Seattle by "hippies" carrying the Viet Cong flag. He was angry, he said, so angry he wanted to run them over. He has mellowed since then. He understands that war is about politics, and that however strong his disagreement with protesters over the issues, "at least they're participating." Not so with Americans who don't vote. "I watched my precinct in the last election," he said. He recalled the precinct having 748 registered voters, and of those, 250 filed for absentee ballots. At 6 p.m., he said, with the polls closing in two hours, only 16 of 498 potential voters had exercised their right to vote. "I have more respect for the protester than I do for that apathy," Ted said. "To cop out is unforgivable." He is certain his friend Bob Dowling, the one who gave his life for such freedoms, would have voted. BOB DOWLING, 41, is a father before he is anything else. He knows the importance of that role, because he didn't have one growing up. His dad wasn't there when he got his master's degree in criminal justice, or when he went to work as a civilian special agent for the Naval Criminal Investigative Service at Sand Point -- the same place his father began his military career. His dad wasn't around to see the assignments Bob got -- protecting Navy admirals, guarding Oliver North during the Iran-contra hearings, protecting Princess Diana when she traveled in the United States. Bob's job has taken him all over the world, protecting classified programs from espionage and providing security for dignitaries. Still, he misses his dad every day. "It gives you perspective, a special understanding," he said. "I'm still learning about grief and how a single person can impact another person.... You never know how big the ripple is going to be. "This story didn't stop Jan. 12, 1966," he said. "The losses of Sept. 11 won't stop there, either. "The substantial loss Sept. 11 ran the entire gamut. It was a massive loss the nation felt. We all felt it. "In a timeline, this is a marker. Just like Pearl Harbor was a marker. Vietnam, for me, was a marker." We're all affected by loss. What matters, Bob said, is how we move beyond what happened to us personally, "how we learn that from a really sad thing, there can be some happiness." BOB AND TED, coming from opposite directions recently, showed up at Fort Lewis in the same instant. Bob wanted to show Ted and Robbie his father's grave. He brought a sponge and a jug of water to clean the headstone. Robbie scrubbed hard to make the writing on his grandpa's stone visible. "I can spell his name without looking," he said, and he did. His dad washed the stone and the three placed roses on the grave and bowed their heads for prayer. "If your dad was here now," Ted said to Bob, "he'd be so proud of you guys. I'm proud of you." And then Robbie ran to the flagpole across the lawn and found the grave of an unknown soldier. Somebody's son or dad is buried there, he told his father.

©

The Seattle Post-Intelligencer

| |||||||||||||

A Note from The Virtual WallThree men of the 197th Assault Helicopter Company were lost when their UH-1B HUEY (hull number 63-08653) went down:

|

|

The point-of-contact for this memorial is his son, Bob Dowling BobbyD115@hotmail.com 26 May 2001 |

|

Top of Page

www.VirtualWall.org Back to |

With all respect

Jim Schueckler, former CW2, US Army

Ken Davis, Commander, United States Navy (Ret)

Last updated 03/02/2006